Containers are a method of operating system virtualization that allow you to run an application and its dependencies in resource-isolated processes. Containers allow you to easily package an application’s code, configurations, and dependencies into easy to use building blocks that deliver environmental consistency, operational efficiency, developer productivity, and version control. Containers are immutable, meaning they help you deploy applications in a reliable and consistent way independent of the the deployment environment.

As containers continue to rise in popularity beyond the developer populous the way these constructs are being used becomes increasingly varied, especially (but not exclusively) in light of enterprise applications the questions of persistent storage comes up more and more. It is a fallacy to think only stateless application can or should be containerized. If you take a look at https://hub.docker.com/explore you’ll see that about half of the most popular applications on Docker Hub are stateful, like databases for example. (Post hoc ergo propter hoc?). If you think about monolithic applications versus micro-services, a monolithic application typically requires state, if you pull this application out into micro-services, some of these services can be stateless containers but others will require state.

I’ll mainly use Docker as the example for this post but many other container technologies exist like LXD, rkt, OpenVZ, even Microsoft offers containers with Windows Server Containers, Hyper-V isolation, and Azure Container Service.

Running a stateless container using Docker is quite straightforward;

$ docker run --name demo-mysql mysql

When you execute docker run, the container process that runs is isolated in that it has its own file system, its own networking, and its own isolated process tree separate from the (local or remote) host.

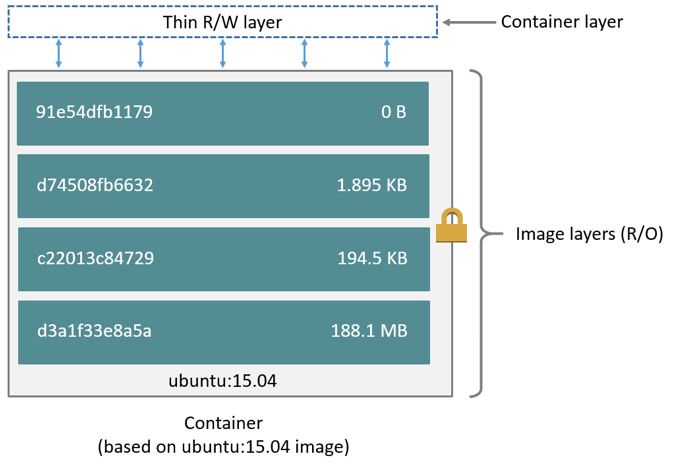

The docker container is created from a readonly template called docker image. The “mysql” part in the command relates to this image, i.e. containerized application, that you want to run by pulling it from the registry. The data you create inside a container is stored on a thin writable layer, called the container layer, that sits on top of the stack of read-only layers, called the image layers, present in the base docker image. When the container is deleted the writable layer is also deleted so your data does not persist , in docker the docker storage driver is responsible for enabling and managing both the read-only image layers and the writable layer, both read and write speeds are generally considered slow.

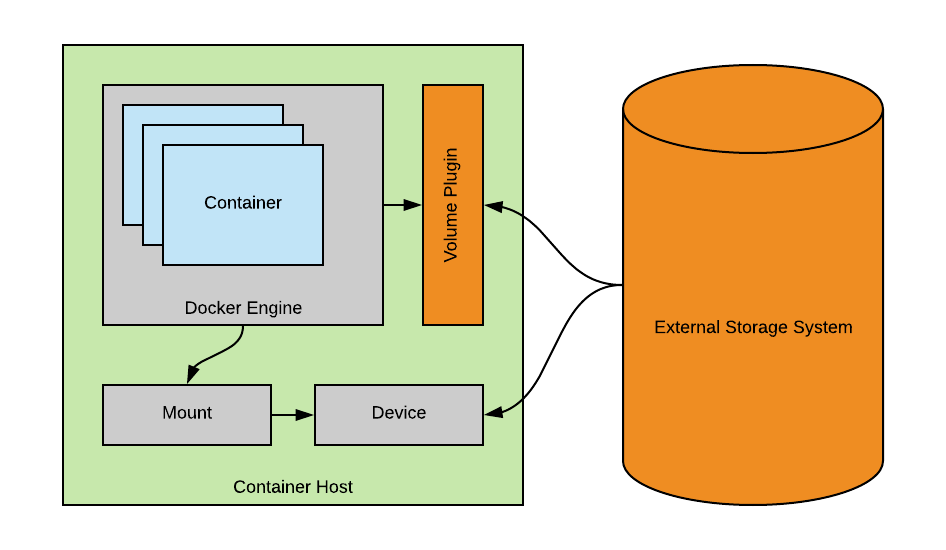

Assuming you want persistent data for your containers there are several methods to go about this. You can add a storage directory to a container’s virtual filesystem and map that directory to a directory on the host server. The data you create inside that directory on the container will be saved on the host, allowing it to persist after the container shuts down. This directory can also be shared between containers. In docker this is made possible by using volumes, you can also use bind mounts but these are dependent on the directory structure of the host machine whereas volumes are completely managed by Docker itself. Keep in mind though that these volumes don’t move with container workloads as they are local to the host. Alternatively you can use volume drives (Docker Engine volume plugins) to store data on remote systems instead of the Docker host itself. If you are only interested in storing data in the container writeable layer (i.e. on the docker host itself) you can use Docker storage drivers which then determine which filesystem is supported.

Typically you would create a volume using the storage driver of your choice in the following manner;

$ docker volume create -—driver=pure -o size=32GB testvol1

And then start a container and attach the volume to it;

$ docker run -ti -v testvol1:/data mysql

Storage Vendors and Persistent Container Storage

Storage vendors have an incentive to make consuming their particular storage as easy as possible for these types of workloads so many of them are providing plug-ins to do just that.

One example is Pure Storage who provide a Docker Volume Plugin for their FlashArray and FlashBlade systems. Current they support Docker, Swarm, and Mesos. Most other big name storage vendors also have plugins available.

Then there are things like REX-Ray which is an open source, storage management solution, it was born out of the now defunct {code} by Dell EMC team. It allows you to use multiple different storage backends and serve those up as persistent storage for your container workloads.

On the virtualization front VMware has something called the vSphere Docker Volume Service which consists of two parts, the Docker Volume Plugin and a vSphere Installation Bundle (VIB) to install on the ESXi hosts. This allows you to serve up vSphere Datastores (be it Virtual SAN, VMFS, NFS based) as persistent storage to your container workloads.

Then there are newer companies that have been solely focusing on providing persistent storage for container workloads, one of them is Portworx. Portworx want to provide another abstraction layer between the storage pool and the container workload. The idea is that they provide a “storage ” container that can then be integrated with the “application” containers. You can do this manually or you can integrate with a container scheduler like Docker Swarm using Docker Compose for example (Portworx provides a volume driver).

Docker itself has built specific plugins as well, Cloudstor is such a volume plugin. It comes pre-installed and pre-configured in Docker swarms deployed through Docker for AWS. Data volumes can either be backed by EBS or EFS. Workloads running in a Docker service that require access to low latency/high IOPs persistent storage, such as a database engine, can use a “relocatable” Cloudstor volume backed by EBS. When multiple swarm service tasks need to share data in a persistent storage volume, you can use a “shared” Cloudstor volume backed by EFS. Such a volume and its contents can be mounted by multiple swarm service tasks since EFS makes the data available to all swarm nodes over NFS.

Container Orchestration Systems and Persistent Storage

As most enterprise production container deployments will utilize some container orchestration system we should also determine how external persistent storage is managed at this level. If we look at Kubernetes for example, that supports a volume plugin system (FlexVolumes) that makes it relatively straightforward to consume different types of block and file storage. Additionally Kubernetes recently started supporting a implementation of the Container Storage Interface (CSI) which helps accelerate vendor support for these storage plug-ins as volume plugins are currently part of the core Kubernetes code and shipped with the core Kubernetes binaries meaning that vendors wanting to add support for their storage system to Kubernetes (or even fix a bug in an existing volume plugin) must align themselves with the Kubernetes release process. With the adoption of the Container Storage Interface, the Kubernetes volume layer becomes extensible. Third party storage developers can now write and deploy volume plugins exposing new storage systems in Kubernetes without having to touch the core Kubernetes code.

When using CSI with Docker, it relies on shared mounts (not docker volumes) to provide access to external storage. When using a mount the external storage is mounted into the container, when using volumes a new directory is created within Docker’s storage directory on the host machine, and Docker manages that directory’s contents.

To use CSI, you will need to deploy a CSI driver, a bunch of storage vendors have these available in various stages of development. For example there is a Container Storage Interface (CSI) Storage Plug-in for VMware vSphere.

Pre-packaged container platforms

Another angle how vendors are trying to make it easier for enterprises to adopt these new platforms, including solving for persistence, is by providing packaged solutions (i.e. making it turnkey), this is not new of course, not too long ago we saw the same thing happening with OpenStack through the likes of VIO (VMware Integrated OpenStack), Platform9, Blue Box (acquired by IBM), etc. Looking at the Public Cloud providers these are moving more towards providing container as a service (CaaS) models with Azure Container Service, Google Container Engine, etc.

One example of packaged container platforms though is the Cisco Container Platform. This is provided as an OVA for VMware (meaning it is provisioning containers inside virtual machines, not on bare metal at the moment), initially this is supported on their HyperFlex Platform which will provide the persistent storage layer via a Kubernetes FlexVolume driver. It then can communicate externally via Contiv, including talking to other components on the HX platform like VMs that are running non containerized workloads. For the load-balancing piece (between k8s masters for example) they are bundling NGINX and for logging and monitoring they are bundling Prometheus (monitoring) and an ELK stack (logging and analytics).

Another example would be VMware PKS which I wrote about in my previous post.

Conclusion

Containers are ready for enterprise use today, however there are some areas that could do with a bit more maturity, one of them being storage. I fully expect to see continued innovation and tighter integrations as we figure out the validity of these use-cases. A lot progress has been made in the toolkits themselves, leading to the demise of earlier attempts like ClusterHQ/Flocker. As adoption continues so will the maturity of these frameworks and plugins.