As an SE at a WAN optimization vendor I’m often faced with the following comment when meeting a new customer: “We don’t need WAN optimization because my ISP is offering me a great deal when I upgrade my bandwidth between A and B”.

Fortunately for me, physics is on my side and the impact of network latency does not go away by increasing the bandwidth. When transmitting a packet from point A to B you are impacted by the time it takes for the packet to travel across the physical network (one-way delay) and get a response back from point B to point A (round trip delay). The packet cannot travel faster than the speed of light and as such your application throughput is depended (a.o. things) on the distance between A and B.

Furthermore the overhead of the protocol we use to transmit data over the WAN is also impacting the performance. Assuming that most applications on your network use TCP, and TCP being a reliability biased (as opposed to performance) protocol, it can seriously impact your throughput.

One of the characteristics of TCP is that it uses a technique called TCP slow start to figure out how much data it can reliably sent across your network.

The diagram below shows TCP slow start in action.

The way it works (simplified, and dependent on the slow start implementation) is that the sender starts out by sending one segment (pkt0 in the diagram) and then waits for the receiver to acknowledge that segment (ACK1) before doubling the number of segments. In other words, initially the sender does not know what the initial value of the congestion window (cwnd) should be so he sets it to 1 (initial window). Each time the sender receives a positive acknowledgement it doubles the number of segments (increases the value of cwnd) it sends out increasing the amount of data transfered at once. The sender controls the congestion window which is the total number of segments sent at one time.

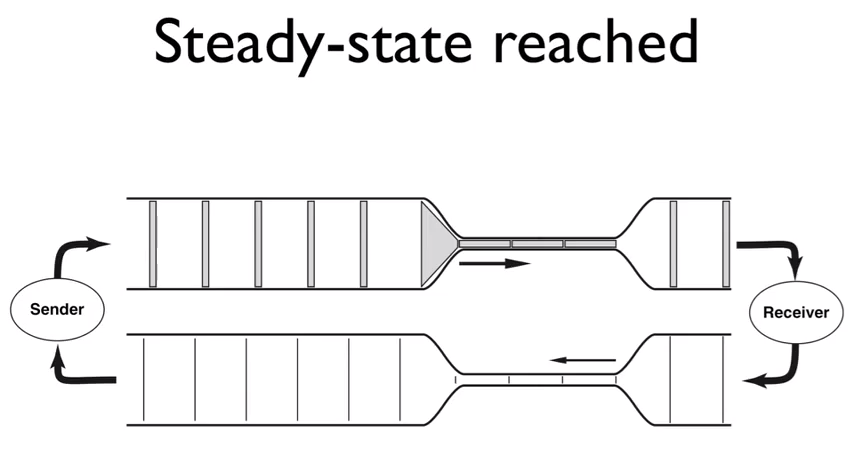

Now lets assume you have a WAN link in the middle, which is the bottleneck in terms of throughput, left to it’s own accord the “clocking” ACKs will settle down (steady-state) the sending rate. (see diagram below).

The total amount of data outstanding (sent segments that did not get an acknowledgment back) needs to fit into the windows size (typically 64K without windows scaling) which is controlled by the receiver. Assuming each data segment is 1460 bytes this means that you can have a maximum of 44 segments unacknowledged at the maximum windows size (again not taking into account windows scaling).

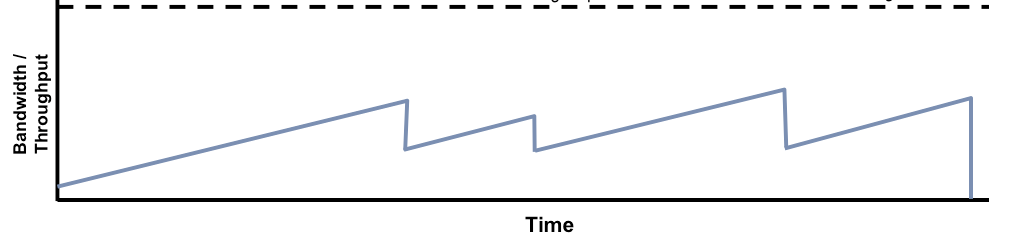

Now when a packet is lost (usually due to congestion in a wired network), congestion control dictates that the sending rate is lowered to 50% of the last value. In other words let’s say at the time of packet loss the cwnd was 8, it will revert to 4 and slow-start will kick in again. Slow start will now not double the segments of the last value (i.e. from 4 to 8) but it will increase the congestion window by 1 segment trying to detect the optimal throughput again leading to a low overall throughput in a high packet loss environment (see diagram below).

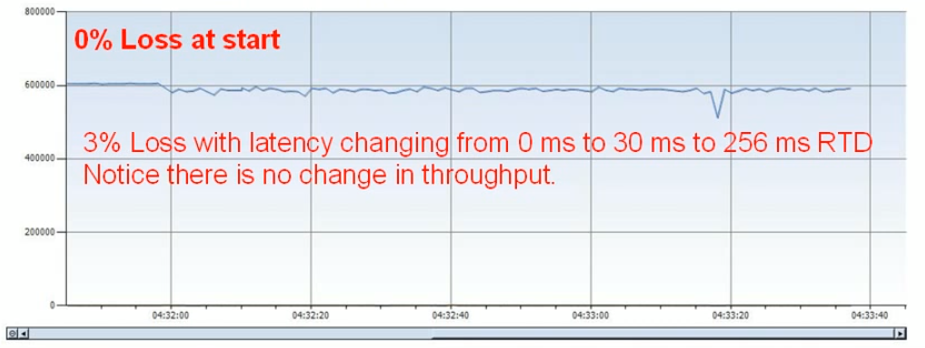

Now let’s look at some actual numbers when introducing packet loss and latency.

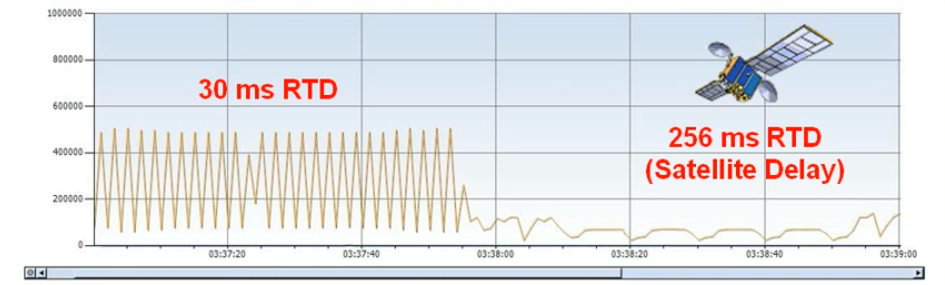

The picture below shows the impact of maximum windows size lenght with a 30ms roundtrip latency on the left, notice that the amount of data going through is constantly being halted because the windows size is full and the sender needs to see the ACK for the maximum outstanding data. (steady state as mentioned above).

On the right side you see the same bandwidth only now the latency has been increased to 256ms roundtrip, the overal throughput drops dramatically even though the bandwidth has not decreased.

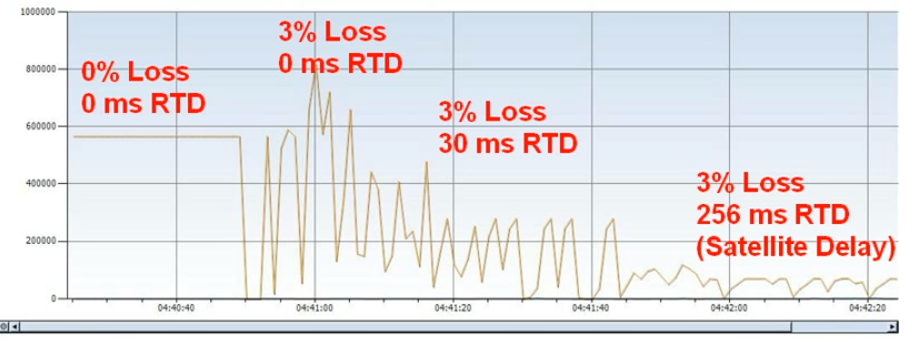

The picture below introduces packet loss, on the left side you have 0% loss and no latency so we get almost full bandwidth utilisation. Next we introduce 3% packet loss and you can see congestion control and slow start struggling to fill the link again even though there is no latency impact. If we then introduce 30ms of roundtrip latency the throughput is impacted by congestion control, slow start and the maximum windows size leading to low link utilization. Lastly on the right we have a satellite simulation with packet loss and high latency completely killing the throughput.

Now as I mentioned before that TCP is biased towards reliability you can see it struggling under certain situations, if we take a look at a protocol that is not bothered by reliability like UDP the picture (see below) completely changes.

Note: this post was meant as an introductory explanation of the effects of packet loss and latency on TCP and is in no way comprehensive, I will cover a lot more details in subsequent posts.